HOW TO BEAT JUMPER’S KNEE

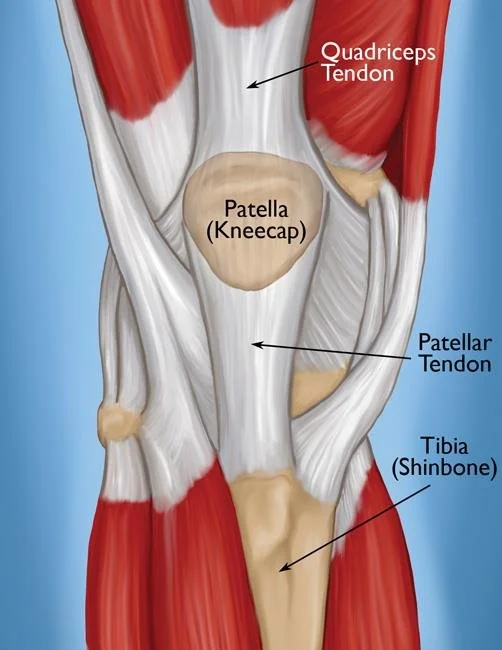

Jumper's knee is a common term used for pain in the prominent tendon which connects the quadriceps muscle group to the front of the tibia (shin bone). This is a continuous tendon with the knee cap embedded in it, but people often refer to the portion above the knee cap as the quadriceps tendon and the portion below as the patellar tendon. You can see an anatomy diagram below as well as what an actual knee looks like under the skin.

Tendon problems are caused when physical stress exceeds the recovery capabilities of the tendon. This can happen in the short term, but the worst cases are the result of frequent high stress athletic activities over time. The body is designed to adapt to physical stress, but these abilities have limits. When people frequently perform many reps of a movement such as jumping that features high tendon stress, breakdown of the tendon can outpace repair. Even if it is ever so slightly, this accumulates over time and results in some portion of the tendon tissue being unhealthy. Often times pain does not show up immediately, or it will just be mild, so the tendon degeneration can go undetected or simply be ignored for a long time until it suddenly presents as a significant problem.

The terms tendinitis, tendinopathy, and tendinosis are all commonly used to describe the unhealthy tissue. I prefer the suffix -osis, which just means “condition,” over -itis (inflammation) or -pathy (disease). The problem we are facing in jumper’s knee is a tendon in an unhealthy condition. So what can we do about it?

There are numerous methods that may be able to create some short-term improvement in pain: icing, pain killers, foam rolling, knee sleeves, flossing, even just warming up. These may help you get through a workout or game, but they do nothing to actually make the tendon healthy again. What we need to do is actually improve the tendon structure by stimulating it to repair and get stronger over time.

Here is the key strategy: Find the right amount of stress that stimulates positive adaptation in the tendon rather than just breaking it down further. Apply that stress consistently and increase it as the tendon gets healthier and stronger.

Here’s a step-by-step process:

STEP 1: STOP JUMPING. It is very difficult for a tendon to heal if it continues to go through high stress athletic activity. Jumps feature a sudden, violent yank on the patellar tendon with peak forces that can exceed 10x body weight (depending on the person and the exact type of jump). Athletes get much faster progress if they stop jumping, and truthfully, it’s best to stop athletic activity in general. Admittedly there are scenarios in which people just do consistent therapeutic exercises on top of their normal athletic activity and still make progress. But this approach slows the process significantly and often creates an endless cycle of short-term improvements followed by setbacks.

STEP 2: DAILY ISOMETRICS. This is the base level of stress to start the healing process. A simple leg extension isometric provides isolated loading of the quadriceps that is steady with no spikes in the force. This makes it the perfect method to find the right entry point for tendon load. A good prescription is 30-45 seconds x 5-6 sets done daily. Use medium to heavy weight, or if pain is a limiting factor, use the pain to guide you. Here is a video: leg extension iso.

STEP 3: STRENGTH TRAINING. As the tendon heals, start using integrated strength training movements like squats and split squats 2-3 times per week while still doing isometrics daily. Start with light weight and move slowly, especially on the descent. As long as the tendon responds positively, gradually increase weight over time. You can also progress to variations that are intentionally hard on the quads like hack squats and skater squats.

STEP 4: PROGRESSIVE ATHLETIC ACTIVITY. Once you know the tendon is handling strength training well, re-introduce athletic activity by starting with low intensity. For example, you could do a small amount of jogging, shuffling, and seated jumps. Then just gradually increase the stress from there. Do the athletic activity just twice per week, so you have time between sessions to make sure the tendon is not responding negatively. And please be patient.

LONG-TERM SOLUTIONS

After you progress back to jumping without pain or any negative response in the following days, here are some guidelines to avoid future tendon problems.

Continue using the strength exercises from the rehab progression to get your quads as strong as possible over time.

Continue using isometrics regularly to provide a therapeutic stimulus to the tendon. This article has not dug into the nitty gritty science on tendons, but isometrics may be uniquely effective for addressing degenerative tissue. I like to use them after jump sessions.

Stretch the rectus femoris. I have not mentioned flexibility so far, because it’s hard to say if or how flexibility influences tendon health. I do tend to believe that being reasonably flexible in general is a good idea. But specifically, the rectus femoris is one of the quadricep muscles and is commonly inflexible. Some people do report that improving flexibility in the RF helps their jumper’s knee. RF stretch.

DON’T JUMP SO MUCH. This is the hard one. Fact is… jumper’s knee typically comes from too much jumping, and it will absolutely come back from too much jumping as well. There is no definitive answer for how much is too much; a lot of factors are at play such as age, weight, strength level, and jumping ability. But generally speaking, an adult who has already had jumper’s knee should not expect to be able to do intense jumping most days of the week without running into pain. Many advanced jumpers limit themselves to one or two days.