GET MORE FAST TWITCH

Muscle fiber type is one of those topics on which people love to make uninformed statements. You may have heard things like, "Heavy weights work those slow twitch fibers." Or "You have to do plyometrics to target quick twitch muscle." Another claim I recall reading as a teenager is that your number of fast twitch fibers is completely genetic and cannot be changed. This is flat out false. Muscle fiber type is adaptable, and this is something that should definitely be taken into consideration in training for explosive athletic performance.

Before getting into that, let's do a quick overview of muscle fiber types. Slow twitch fibers produce less tension and take more time to reach peak tension but possess excellent endurance. Fast twitch fibers produce greater tension and reach peak tension more quickly but have very little endurance. Having more slow twitch fibers is helpful for endurance activities. On the other hand, possessing a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers is advantageous for any activity that involves maximum force production such as sprinting, jumping, and yes, heavy lifting. Because heavy strength training features high muscle tension, it's actually a fast twitch dominant activity. There is a continuum of fiber types from slow to fast, but we have classified them into three primary types, Type 1 (slow), Type 2A (semi-fast), and Type 2B (fast). A muscle fiber's type is identified by the chemical composition of the head of the myosin protein molecules within the fiber. Myosin heavy chain I, IIA, and IIX are associated with type 1, type 2A, and type 2B fibers respectively. This does not mean that a fiber exclusively contains just one type of myosin.

Fiber Type Change

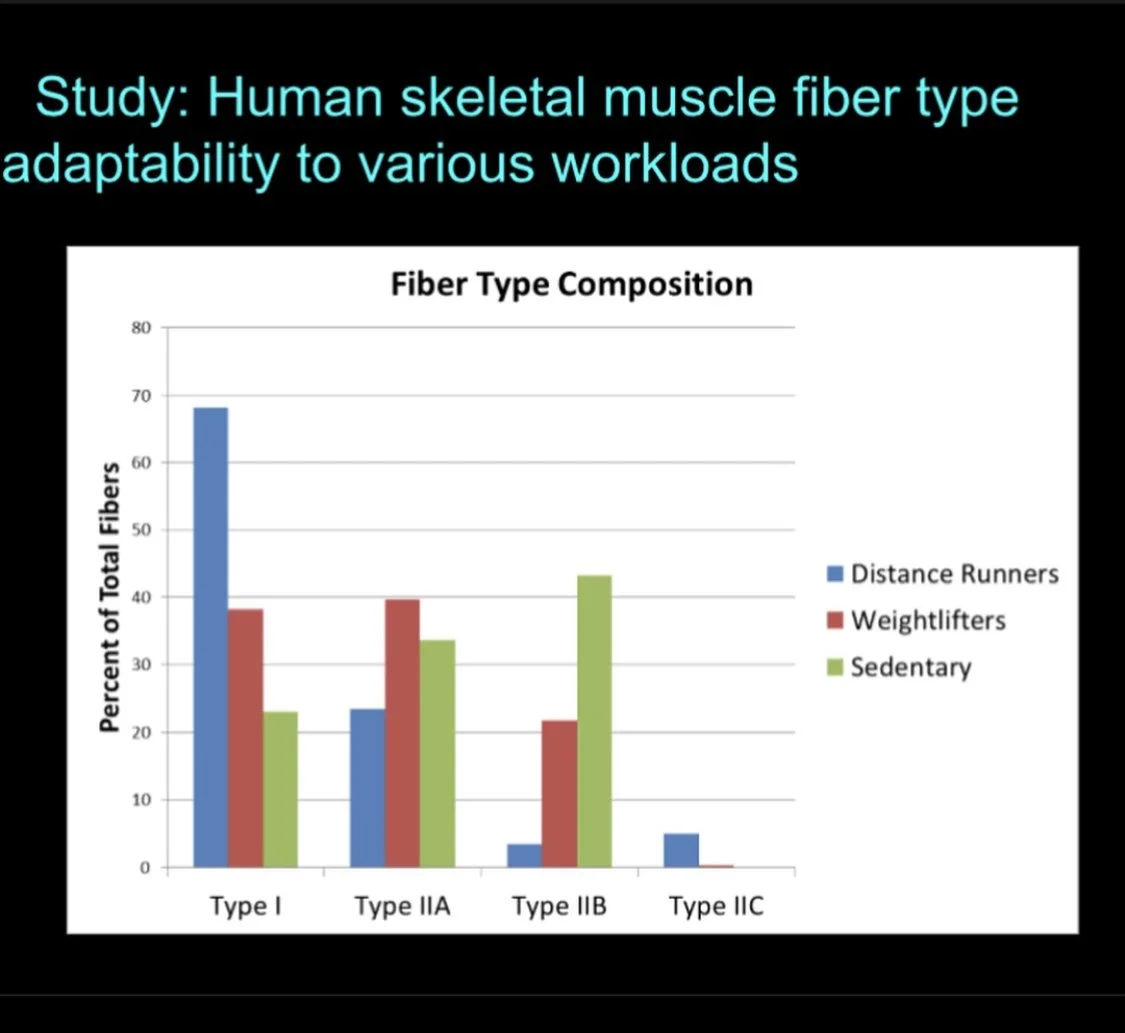

Fiber twitch speed is adaptable. It is shaped by activity over time. People may expect this to simply mean that endurance activities yield more slow twitch fibers and maximal effort activities yield more fast twitch fibers. And this does appear to be true if we just compare endurance athletes and strength athletes for example. However, when we look at sedentary people, we find that they tend to have more fast twitch fibers than anybody. The graph below shows average fiber type distribution among a small group of runners, strength athletes, and sedentary people. The full study is here: Human Skeletal Muscle Fiber Type Adaptability. What this tells us is that a need for greater force production is not the defining stimulus that influences muscle fiber type changes. Rather it is a need for endurance. Sedentary people have no need for endurance, so their muscle fibers default toward being fast twitch.

Is It All Genetics?

Skeptics of fiber type changes may suggest that the differences between athletes in different sports exist at birth and cause each person to naturally excel in the sport they end up pursuing. While genetics certainly do influence muscle fiber types, a high level of adaptability is clearly evident. In fact the next study examined numerous drastic differences, including fiber types, between genetically identical twins with very different histories of exercise. Muscle Health and Performance in Monozygotic Twins. The graphs below show the major differences in fiber type distribution that developed over time between the sedentary and endurance trained twin. You can see that over time the endurance activity yielded far more slow twitch fibers compared to being sedentary. This makes sense.

IIX Switch-off

The next piece of evidence is a bit counterintuitive. Rapid Switch-off of the Human Myosin Heavy Chain IIX Gene. In this study sedentary subjects performed just two consecutive days of strength training. In the days following, the gene for myosin IIX (the fastest one) shut off, so to speak. This does not mean that the fibers converted to type 2A already in four days. The actual changes to the protein molecules would have followed later. But the key point here is strength training, even though it is fast twitch dominant, actually caused a shift toward slower twitch speed compared to being sedentary. Now let's be clear. This does not mean that these research subjects would get less athletic from strength training. If they combined some sort of athletic activity with strength training, most likely the gains in neuromuscular strength would far outweigh the influence of type 2B fibers shifting to type 2A. In that scenario these subjects would see drastic improvement in athletic measures. But we still need to make note of the influence of strength training on fiber type.

IIX Overshoot

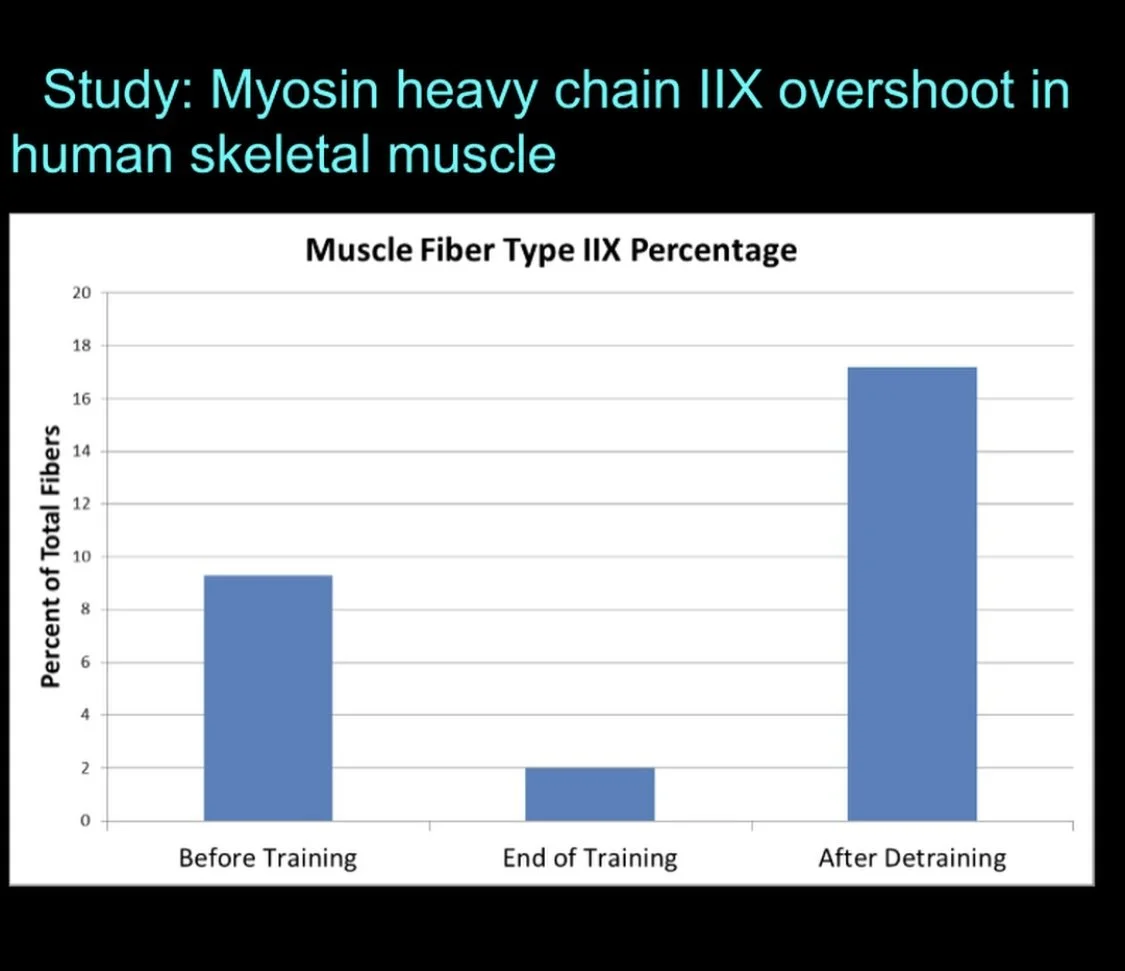

Next we come to one of my favorite topics in all of sports training, the overshoot phenomenon. The research: Myosin Heavy Chain IIX Overshoot. Just like in the previous study, sedentary subjects performed heavy resistance training, this time for three months. At the end of the training, many of the myosin IIX molecules had converted to myosin IIA. This lines up with the results from the previous study. But then the subjects returned to being sedentary, and after three months of detraining myosin IIX content had shot up well beyond the initial level (graph below). This is known as the overshoot phenomenon. Again, let's be clear. This does not mean that the subjects were more athletic after three months of detraining. The loss of neuromuscular strength from long term inactivity far outweighs the fiber type changes. The overshoot phenomenon refers specifically to the increase in myosin IIX content. It does not refer to an increase in athleticism. Muscle fiber type is just one factor in athleticism.

The overshoot phenomenon was replicated in this study: Changes in the human muscle force-velocity relationship. Again, subjects did three months of resistance training followed by three months of de-training, which produced a loss and then overshoot of myosin IIX content. This study also used several performance measurements of knee extension at different speeds. The de-training resulted in a loss of strength gains in resisted knee extension as expected, but this was accompanied by clear enhancements of unresisted knee extension as measured by acceleration, velocity, force and power at high velocity, and rate of force development. The influence of the fast twitch overshoot is obvious.

APPLICATION

The research on fiber type adaptation is interesting, but how do we harness this knowledge to get more athletic? None of the studies use realistic protocols for athletes; avoiding exercise for three months is not a viable training strategy. So how do we translate the data from this research into something practical? An easy takeaway would be the common principle of not over-training and getting adequate recovery. Of course we could make those recommendations without ever mentioning fiber types. General recovery is not easy to measure physiologically, so in some sense maybe fiber type gives us a sort of proxy measurement, but there is certainly a distinction. Myosin IIX overshoot after months of de-training is not the same thing as general recovery. Thus, I believe we can glean more from the data on fiber typing than just a generic prescription to take some off days.

The key principle to grasp is that muscle fibers shift toward slow twitch characteristics when more endurance is required and default toward more fast twitch characteristics when rested. And even among fast-twitch activities, there is a distinction between training for strength (myosin IIA) vs explosive performance (myosin IIX). This is a reason to limit endurance training, avoid over-training, be strategic with strength training, and seek out opportunities for rest in the training process. This of course has to be balanced with the need to put in work, get strong, and play a sport frequently. What does that balance look like? We could speculate about a thousand different contexts and training strategies, but I’ll try not to ramble on too much.

If we just wanted to be as fast twitch as possible, we would use only high intensity and low volume 2-3 days per week. We would avoid any conditioning and take breaks from strength training to exclusively sprint and jump. And we would even take breaks from athletic activity entirely in order to harness the overshoot phenomenon. There are certainly anecdotes of athletes having success with these strategies. For some people, it can be uncomfortable to learn that a small amount of work can be effective; it is important to acknowledge these cases. However, it is also critical to understand that this low volume approach to training is really only suitable for certain contexts.

Consider life stages. Young kids build their athletic foundation through a high volume of athletic activity. It is a necessary component of early development. Important physical traits such as coordination, tissue durability, elasticity, sport specific skill, and cardiovascular fitness depend on this. With that in mind, young kids generally should be doing athletic things every day and do not need to be concerned with maximizing their fast twitch fibers. (Side note: Athletic activity for young kids should be diverse and mostly fun rather than practicing one sport exhaustively all week long.)

Consider different types of people. This is based on experience and somewhat speculative, but low volume training may be most effective for athletes that have a fair amount of fast twitch fibers to begin with. Think of the naturally explosive athlete that doesn’t love to work out and has bad endurance. Low volume might be less effective for natural workhorse athletes as well as most females (who generally do not have as many fast twitch fibers).

And lastly keep in mind that fiber twitch speed is only one factor in athleticism and sporting success. As already stated, there are many physical qualities that athletes need in varying degrees which require a lot of work to develop. I certainly would not tell a 400m sprinter that she will run her best race by only training twice per week during track season. I certainly would not tell a basketball player that he should only be on the court twice per week all year long. Athletes obviously have many things they must do besides just maximize fast twitch capabilities.

With all that in mind, a general recommendation is simply balancing out higher volume, harder training periods with lower volume or easier periods. For a hypothetical example, consider a college sprinter.

The track team presumably has practice or competition 4-6 days per week for much of the fall and spring, including plenty of hard running days. This is necessary to get elastic volume. Within this stretch of training, avoiding excessive conditioning and using easier weeks are strategies to improve training quality and perhaps preserve some fiber twitch speed.

The holidays present an opportunity to take advantage of more rest days. You would not want to de-train at this time, so some maintenance work is needed.

Toward the end of the season, cutting down training volume and taking more days off allows all the work to come to fruition and produces records on the track.

Following track season, the sprinter will likely benefit from taking a couple weeks away from intense training.

The next phase might be a general athletic development period in which improved strength, power, and jumping are the goal. This pursuit will likely be more successful if conditioning is avoided and workouts are limited to three days per week. Let’s say that approach is used for three months. This would set up the sprinter to enter fall training again as a stronger and more explosive athlete, which should translate to faster times the next spring after they go through the whole track training process again.

High volume strength training, if it’s necessary at all, can be used earlier in the training year, low volume or possibly no strength training later. Even in a higher volume period, the requirement for endurance in the weight room can be minimized. An example of how to do this is using cluster sets instead of high-rep sets (Ex. 8x4 instead of 3x10).

ANECDOTES

A long jumper I worked with is a great example. (1) When Dillon first started training with me in the summer, he got fast results training just twice per week. (2) In the back half of track season, he was fatigued from tons of running for team relays, so he did very little training in the two weeks leading up to the state meet. At state he hit a long jump personal record by 6 inches. It was 14 inches longer than what he was jumping in the second half of the season while fatigued. (3) After the state meet, Dillon did not work out for 6 weeks straight. When he began training again, he returned to his highest max velocity ever within 12 days. Here is a recap of that year of training: Long Jump Case Study.

Check out this Instagram post on the training of triple jump world record holder, Jonathan Edwards. Did you know he was forced to take 6 months off training the year before his world record jumps?

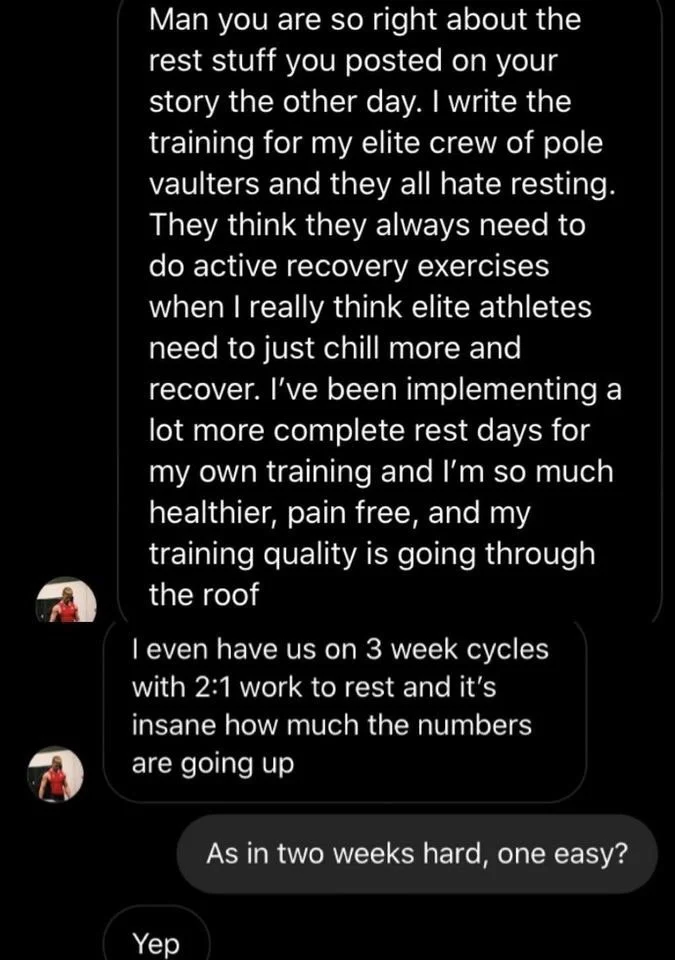

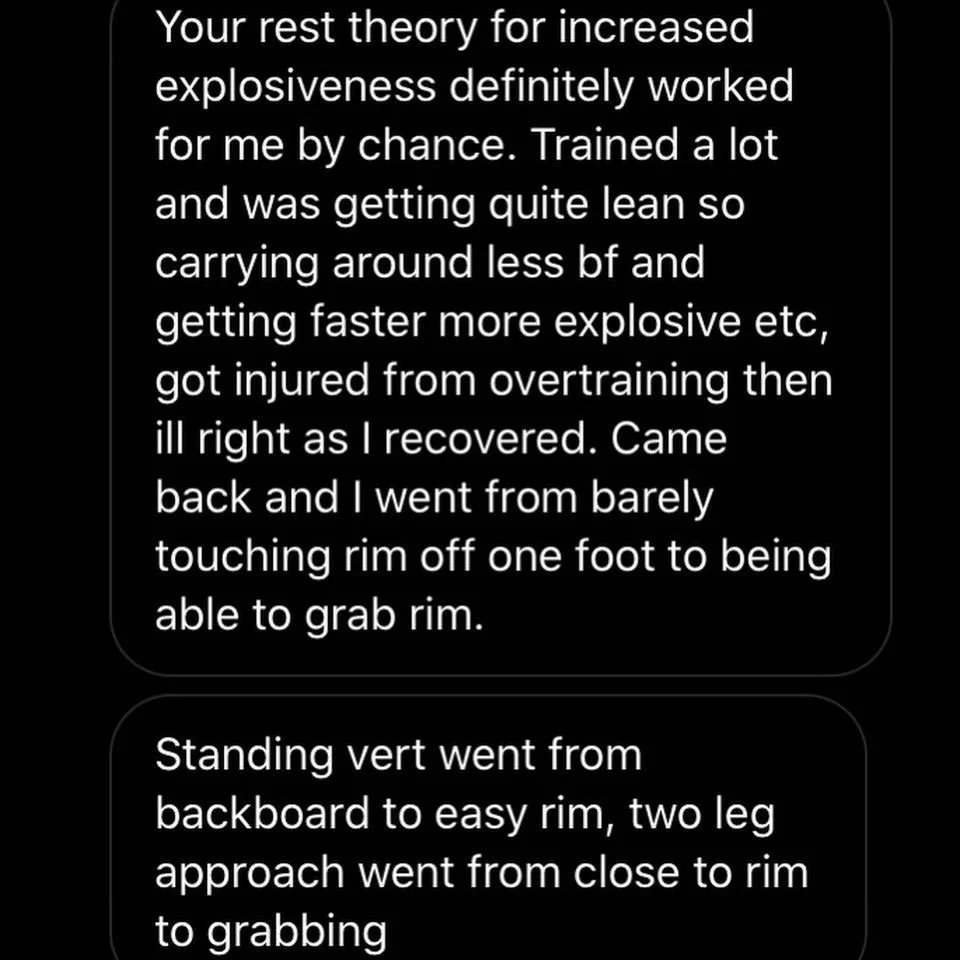

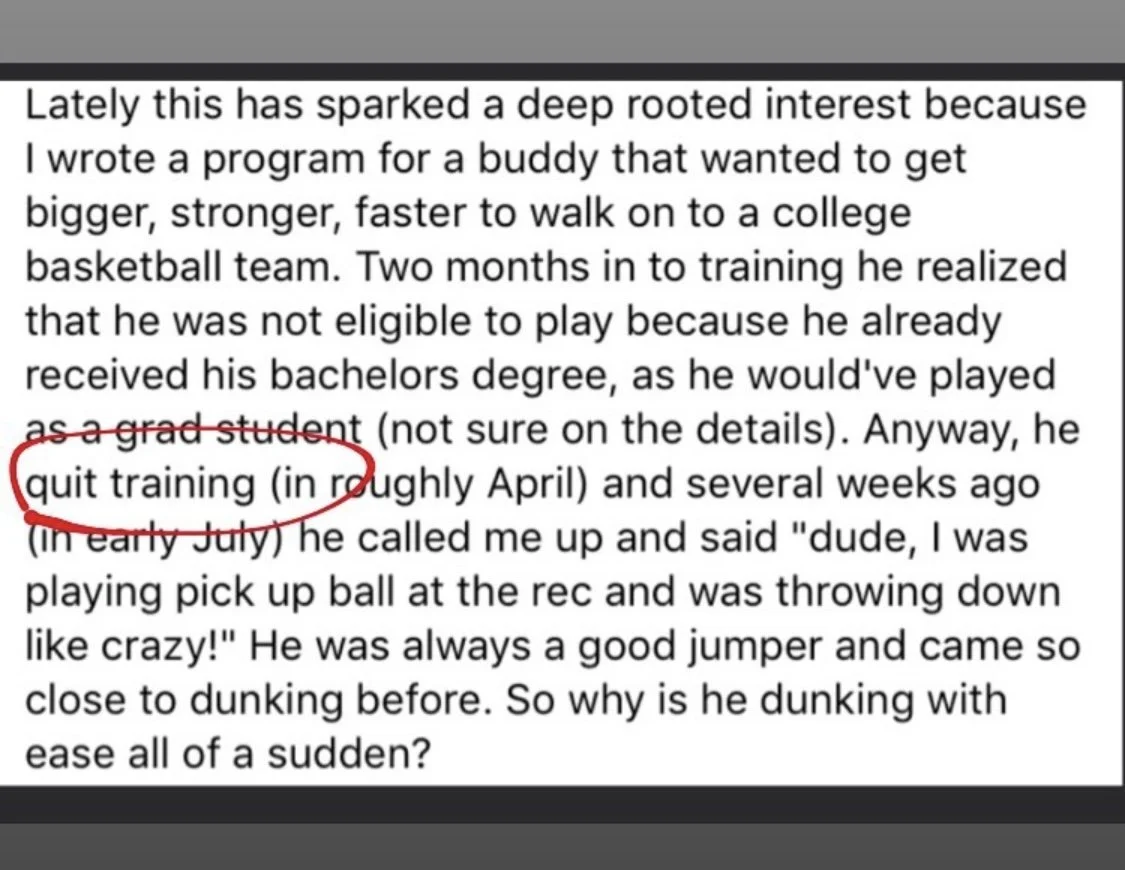

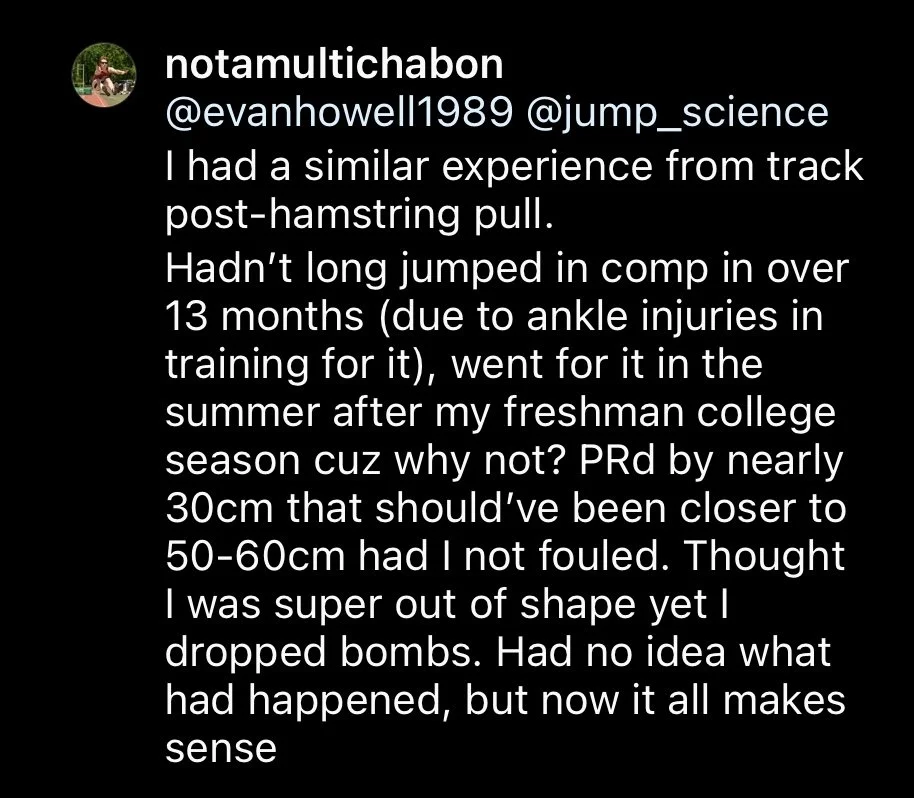

Also check out the stories shared in the pics below. Learn to do less, my friends!

2X ATHLETE PROGRAMS